It's that sudden STOP!!!

Soo I was going through my Facebook feed this week and came across this bit of information that rocked my work. I always remind my self that because it is written does not mean it is all true but you ready this except and you decide if you think its true.

What caught my eye was the title: HOW THE BAHAMAS BECAME THE BAHAMAS, WITH A LITTLE HELP FROM SOME VERY STRANGE MEN .... AND CANADA.

Hmmm I thought. Very interesting. Then I saw the length of the article and immediately thought it was going to be boring.

Well I was left trying to buy the book.

If you dont hear from me for a while, I'm still contemplation ways forward.

Posted: June 25, 2013 Filed under: Insights, Jeffrey Robinson's eBooks, Money Laundering Comments Off on HOW THE BAHAMAS BECAME THE BAHAMAS, WITH A LITTLE HELP FROM SOME VERY STRANGE MEN… AND CANADA

Rich Americans had wintered in the Bahamas and sports fishermen had plied the waters there for years. But in the mid-1950s, tourism in the islands was a far cry from what it is today. For that to develop, there had to be an infrastructure. And the story of how that infrastructure evolved — how the pieces got put into place for the Mob — is filled with a cast of screwballs and eccentrics, any one of whom could have come straight off the pages of Damon Runyan.

The story begins with a swindler from Baltimore named Wallace Groves who first showed up during the Great Depression and lived in the Bahamas on and off — the notable off period being 1941-1944 when his residence was a US federal prison — for most of his adult life. A man who was forever dreaming up schemes that entailed bilking the local treasury, his partner in crime was Sir Stafford Sands, a Bahamian attorney and power broker who stroked the heart of the white minority “Bay Street Boys” government. Conveniently, Sands was also chairman of the Development Board which, effectively, made him the minister for tourism.

More than just “vaguely villainous”, as some Bahamians remember him today, Sands was thoroughly corrupt. He was also a bigot who would leave his country when black majority rule was introduced, to die in stubborn exile in 1972 at London’s Dorchester Hotel. And yet, his legacy as the architect of the island’s modern economy is such that his oval, spectacled face stares back from the Bahamian ten dollar bill.

Sands’ strategy to bring the islands into the 20th Century — while all the time insuring his own financial security — saw Groves play the front man. In 1955, the two men applied for a government grant of 50,000 acres, all sorts of tax breaks plus the promise of more land, to create the Grand Bahama Port Authority. Needless to say, the scheme was approved. But when Sands admitted that this was far too substantial a project to pull off on their own, he and Groves fast-talked the enigmatic Daniel K. Ludwig into backing them.

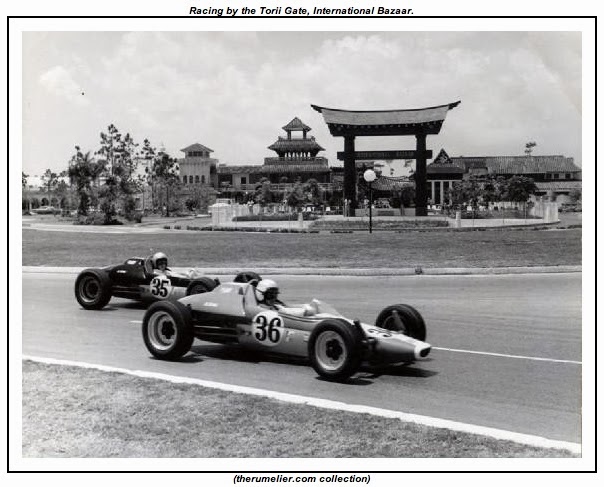

A postwar financier who showed up on everybody’s “richest men in captivity” list, Ludwig owned the world’s largest merchant shipping fleet and therefore had the wherewithal to guarantee the project’s success. He dug the harbor while Groves and Sands developed the land. The result was Freeport, the Caribbean’s first significant industrial center and purpose built parking lot for cruise ships. Groves and Sands next step was to parlay Freeport into a tourist resort. For that, Groves brought in a Canadian conman friend named Lou Chesler.

Known as “Moose”, because he weighed nearly 300 pounds and looked like one, Chesler made his first million in 1946, at the age of 33, flogging dodgy Canadian mining stocks. He took his money to Florida, sold swamps to the gullible, bought dry land for himself and by 1960 had multiplied his fortune fifty fold. Along the way, he went out to Hollywood, bought Associated Artists, named himself chairman and, through various share manipulations, turned one company into another to become chairman of Seven Arts. Chesler had learned the art of duplicity back in the early “40s from a skilful fraudster named John Pullman.

Born in Russia, Pullman spent his early years in Canada, emigrated to the States and, after serving in the US Army, wound up in Chicago bootlegging whisky. In 1931, he was convicted for violations of the Volstead Act and served six months. While in jail, Pullman met a rumrunner from Minneapolis named Yiddy Bloom. When they both got out, Bloom introduced his new friend Pullman to his old friend Meyer Lansky and, some years later, Pullman introduced his new friend Lansky to his old friend, Lou Chesler.

Chesler and Lansky hit it off and worked several scams together, most notably injecting Mob money into the 1958 redevelopment of Miami International Airport. So now, when Groves brought Chesler into the Freeport project, Chesler arrived holding hands with Lansky.

In the meantime, Pullman concluded that he didn’t like being an American criminal any more, so he gave up his citizenship to become a Canadian criminal. Except, he didn’t like the Canadian weather, so he moved to Switzerland where he hooked up with the intensely mysterious Tibor Rosenbaum.

A Holocaust survivor, Rosenbaum was either an agent for the Israeli intelligence service Mossad, or a businessman whom Mossad could call on for favors. The extent of his service has never been made clear and probably never will be. It is known that, between the end of World War II in 1945 and mid-1948, Rosenbaum ran guns from Czechoslovakia to Palestine. He is remembered today as one of those men who helped forge Israeli statehood. It is also known that, at some point over the following ten years, Rosenbaum spent a great deal of time in — of all bizarre places — Liberia. After doing whatever it was he did there, by the time he moved to Geneva, Rosenbaum was carrying a black diplomatic passport as an Honorary Counsel of Liberia.

In 1959, almost certainly with Mossad backing, Rosenbaum created the Banque International de Credit (BIC) which was to become a legendary laundry. Liberian diplomatic passports would also, in their own way, become part of the offshore world’s myth.

So Pullman joined Rosenbaum in Geneva while Chesler, in the Bahamas, formed a company called Devco which acquired land from Groves’ and Sands’ Port Authority in exchange for Devco shares. Chesler then folded Devco into a pair of bogus Canadian shell companies and announced plans to build the deluxe Lacayan Beach Hotel. Incongruously, included in the blueprints for a hotel where people would be spending most of their time outside on the beach in perfect weather, were several large indoor squash courts.

Despite having failed to attract enough tourists to support Chesler’s resort, Sands formed a company with Chesler and Groves called Bahamas Amusement. The ink was still wet on the incorporation documents when the government granted Bahamas Amusement — part owned by the man in charge of tourism — an exclusive ten-year license to operate casinos on the island. Seconds later, miraculously, by connecting a few dots on the Lacayan’s blueprints, the squash courts became the Monte Carlo casino.

It was opened in January 1964, several weeks before the hotel itself was completed. Lansky bankrolled it and put in his own guy, Dino Cellini, to supervise it. When the deceit, conflicts and corruption became too obvious even by Bahamian standards, when Sands’ puppets in government “suddenly realized” that the country was overflowing with mobsters, Premier Roland Symonette ordered out a handful of the most prominent goons, with Cellini heading the list. But the extradition paperwork conveniently got lost in the bureaucratic maze and everyone, except Cellini, was allowed to stay for up to four years. Lansky sent Cellini to England, where he joined his brother Eddie in the background of the Colony Club, one of London’s most notorious casinos. Fronted by actor George Raft, Dino and Raft were eventually declared undesirables and tossed out of the UK.

No sooner was the Monte Carlo up and running when John Pullman moved from Geneva to Freeport to open the Bank of World Commerce (BWC). Years later, the New Jersey Casino Control Commission would describe BWC as a sink for “some of the nations” top gangsters where “millions of dollars passed through the door and were reinvested in syndicate controlled projects in the United States.”

The casino skim from Vegas now mingled with casino skim from the Bahamas and moved through BWC on its way to BIC in Switzerland. To oil the works, Rosenbaum opened a local subsidiary of BIC in Freeport called Atlas Bank. He then turned to Africa, to help despots there bring stolen booty into the West, laundering it through BIC and Atlas and, from the Bahamas, investing it for them in North America. Not to be left out in his own backyard, Stafford Sands opened a bank in Nassau called Intra Bahamas Trust Ltd, which was tied to Intra Bank of Beirut, headquartered in Lebanon, which is one of the world’s most under-rated drug money laundering centers.

Enter here the hapless George Huntington Hartford II.

A man born with a $90 million silver spoon in his mouth, he was heir to the A&P grocery store empire. Hartford was also a man struggling to make his own dreams come true. By the time he’d graduated Harvard in 1934, he’d dropped the George and replaced the II with tags such as art collector, museum benefactor, magazine publisher, author and property developer. The problem was that, most of the time, he lost money and by the end of his life he’d gone through a sizeable amount of his fortune.

In the early 1950s, Hartford had “discovered” a 700-acre beach ten minutes by boat from Nassau called Hog Island. Measuring four miles by two-thirds of a mile, it got its name because it was overrun with pigs. Hartford bought it the same day he spotted it, never thinking it might be a good idea if his lawyers come down first to read the small print on his $11 million purchase. Hartford intended to develop the place into one of the world’s great tourist resorts. He renamed it Paradise Island and, over the next several years, dropped another $19 million trying to make it look like its new namesake.

At the heart of his plans was a hotel and casino complex. At the heart of his downfall was the fact that he chose the wrong law firm to advise him. Instead of going with Stafford Sands, he opted for honest lawyers and was, therefore, never able to acquire the necessary gaming license. Compounding the sin, Hartford sank money into the underdog, black power Progressive Liberal Party, which was tantamount to treason in the eyes of Sands and his white United Bahamians.

That Hartford soon ran into cash flow troubles simply exposed his carcass to the circling vultures. He was forced to sell part of his interest for $750,000. Inexplicably, Hartford then turned around and lent $2 million to the man who’d bought that part interest, accepting repayment in unregis tered stock, which he quickly discovered he couldn’t sell to anyone. So his new partner — the same fellow who still owed him $2 million — offered to help out with a $1 million loan, which wound up being secured with another hefty chunk of Paradise Island shares. The original guarantees were quickly pulled and the loan was called in. Hartford’s stake was sold and the net result was that his $30 million investment in Paradise Island produced a $28 million tax loss.

The group that moved in on Paradise Island was called Mary Carter Paint. They’d already tied up with Groves and Chesler in Freeport and would, in time, evolve into Resorts International. With Sands help, it was Mary Cater Paint that secured the casino license and saw Paradise Island rise out of Hartford’s ashes.

Lansky, in the meantime, was feeling the all-too familiar chill of political change. So he followed Hartford’s lead by quietly backing the Progressive Liberals. By the time the black Bahamian opposition just-barely squeaked into power in 1967, Sands was on his way into exile and the island’s new leader — Lynden Pindling — was on his way into the pocket of the great survivor, Meyer Lansky.

KINDLE: THE SINK http://amzn.to/132O2cE

What caught my eye was the title: HOW THE BAHAMAS BECAME THE BAHAMAS, WITH A LITTLE HELP FROM SOME VERY STRANGE MEN .... AND CANADA.

Hmmm I thought. Very interesting. Then I saw the length of the article and immediately thought it was going to be boring.

Well I was left trying to buy the book.

If you dont hear from me for a while, I'm still contemplation ways forward.

Posted: June 25, 2013 Filed under: Insights, Jeffrey Robinson's eBooks, Money Laundering Comments Off on HOW THE BAHAMAS BECAME THE BAHAMAS, WITH A LITTLE HELP FROM SOME VERY STRANGE MEN… AND CANADA

EXCERPT FROM:

“THE SINK – Terror, Crime and Dirty Money in the Offshore World”

(C) JEFFREY ROBINSON 2003, 2011

Rich Americans had wintered in the Bahamas and sports fishermen had plied the waters there for years. But in the mid-1950s, tourism in the islands was a far cry from what it is today. For that to develop, there had to be an infrastructure. And the story of how that infrastructure evolved — how the pieces got put into place for the Mob — is filled with a cast of screwballs and eccentrics, any one of whom could have come straight off the pages of Damon Runyan.

The story begins with a swindler from Baltimore named Wallace Groves who first showed up during the Great Depression and lived in the Bahamas on and off — the notable off period being 1941-1944 when his residence was a US federal prison — for most of his adult life. A man who was forever dreaming up schemes that entailed bilking the local treasury, his partner in crime was Sir Stafford Sands, a Bahamian attorney and power broker who stroked the heart of the white minority “Bay Street Boys” government. Conveniently, Sands was also chairman of the Development Board which, effectively, made him the minister for tourism.

More than just “vaguely villainous”, as some Bahamians remember him today, Sands was thoroughly corrupt. He was also a bigot who would leave his country when black majority rule was introduced, to die in stubborn exile in 1972 at London’s Dorchester Hotel. And yet, his legacy as the architect of the island’s modern economy is such that his oval, spectacled face stares back from the Bahamian ten dollar bill.

Sands’ strategy to bring the islands into the 20th Century — while all the time insuring his own financial security — saw Groves play the front man. In 1955, the two men applied for a government grant of 50,000 acres, all sorts of tax breaks plus the promise of more land, to create the Grand Bahama Port Authority. Needless to say, the scheme was approved. But when Sands admitted that this was far too substantial a project to pull off on their own, he and Groves fast-talked the enigmatic Daniel K. Ludwig into backing them.

A postwar financier who showed up on everybody’s “richest men in captivity” list, Ludwig owned the world’s largest merchant shipping fleet and therefore had the wherewithal to guarantee the project’s success. He dug the harbor while Groves and Sands developed the land. The result was Freeport, the Caribbean’s first significant industrial center and purpose built parking lot for cruise ships. Groves and Sands next step was to parlay Freeport into a tourist resort. For that, Groves brought in a Canadian conman friend named Lou Chesler.

Known as “Moose”, because he weighed nearly 300 pounds and looked like one, Chesler made his first million in 1946, at the age of 33, flogging dodgy Canadian mining stocks. He took his money to Florida, sold swamps to the gullible, bought dry land for himself and by 1960 had multiplied his fortune fifty fold. Along the way, he went out to Hollywood, bought Associated Artists, named himself chairman and, through various share manipulations, turned one company into another to become chairman of Seven Arts. Chesler had learned the art of duplicity back in the early “40s from a skilful fraudster named John Pullman.

Born in Russia, Pullman spent his early years in Canada, emigrated to the States and, after serving in the US Army, wound up in Chicago bootlegging whisky. In 1931, he was convicted for violations of the Volstead Act and served six months. While in jail, Pullman met a rumrunner from Minneapolis named Yiddy Bloom. When they both got out, Bloom introduced his new friend Pullman to his old friend Meyer Lansky and, some years later, Pullman introduced his new friend Lansky to his old friend, Lou Chesler.

Chesler and Lansky hit it off and worked several scams together, most notably injecting Mob money into the 1958 redevelopment of Miami International Airport. So now, when Groves brought Chesler into the Freeport project, Chesler arrived holding hands with Lansky.

In the meantime, Pullman concluded that he didn’t like being an American criminal any more, so he gave up his citizenship to become a Canadian criminal. Except, he didn’t like the Canadian weather, so he moved to Switzerland where he hooked up with the intensely mysterious Tibor Rosenbaum.

A Holocaust survivor, Rosenbaum was either an agent for the Israeli intelligence service Mossad, or a businessman whom Mossad could call on for favors. The extent of his service has never been made clear and probably never will be. It is known that, between the end of World War II in 1945 and mid-1948, Rosenbaum ran guns from Czechoslovakia to Palestine. He is remembered today as one of those men who helped forge Israeli statehood. It is also known that, at some point over the following ten years, Rosenbaum spent a great deal of time in — of all bizarre places — Liberia. After doing whatever it was he did there, by the time he moved to Geneva, Rosenbaum was carrying a black diplomatic passport as an Honorary Counsel of Liberia.

In 1959, almost certainly with Mossad backing, Rosenbaum created the Banque International de Credit (BIC) which was to become a legendary laundry. Liberian diplomatic passports would also, in their own way, become part of the offshore world’s myth.

So Pullman joined Rosenbaum in Geneva while Chesler, in the Bahamas, formed a company called Devco which acquired land from Groves’ and Sands’ Port Authority in exchange for Devco shares. Chesler then folded Devco into a pair of bogus Canadian shell companies and announced plans to build the deluxe Lacayan Beach Hotel. Incongruously, included in the blueprints for a hotel where people would be spending most of their time outside on the beach in perfect weather, were several large indoor squash courts.

Despite having failed to attract enough tourists to support Chesler’s resort, Sands formed a company with Chesler and Groves called Bahamas Amusement. The ink was still wet on the incorporation documents when the government granted Bahamas Amusement — part owned by the man in charge of tourism — an exclusive ten-year license to operate casinos on the island. Seconds later, miraculously, by connecting a few dots on the Lacayan’s blueprints, the squash courts became the Monte Carlo casino.

It was opened in January 1964, several weeks before the hotel itself was completed. Lansky bankrolled it and put in his own guy, Dino Cellini, to supervise it. When the deceit, conflicts and corruption became too obvious even by Bahamian standards, when Sands’ puppets in government “suddenly realized” that the country was overflowing with mobsters, Premier Roland Symonette ordered out a handful of the most prominent goons, with Cellini heading the list. But the extradition paperwork conveniently got lost in the bureaucratic maze and everyone, except Cellini, was allowed to stay for up to four years. Lansky sent Cellini to England, where he joined his brother Eddie in the background of the Colony Club, one of London’s most notorious casinos. Fronted by actor George Raft, Dino and Raft were eventually declared undesirables and tossed out of the UK.

No sooner was the Monte Carlo up and running when John Pullman moved from Geneva to Freeport to open the Bank of World Commerce (BWC). Years later, the New Jersey Casino Control Commission would describe BWC as a sink for “some of the nations” top gangsters where “millions of dollars passed through the door and were reinvested in syndicate controlled projects in the United States.”

The casino skim from Vegas now mingled with casino skim from the Bahamas and moved through BWC on its way to BIC in Switzerland. To oil the works, Rosenbaum opened a local subsidiary of BIC in Freeport called Atlas Bank. He then turned to Africa, to help despots there bring stolen booty into the West, laundering it through BIC and Atlas and, from the Bahamas, investing it for them in North America. Not to be left out in his own backyard, Stafford Sands opened a bank in Nassau called Intra Bahamas Trust Ltd, which was tied to Intra Bank of Beirut, headquartered in Lebanon, which is one of the world’s most under-rated drug money laundering centers.

Enter here the hapless George Huntington Hartford II.

A man born with a $90 million silver spoon in his mouth, he was heir to the A&P grocery store empire. Hartford was also a man struggling to make his own dreams come true. By the time he’d graduated Harvard in 1934, he’d dropped the George and replaced the II with tags such as art collector, museum benefactor, magazine publisher, author and property developer. The problem was that, most of the time, he lost money and by the end of his life he’d gone through a sizeable amount of his fortune.

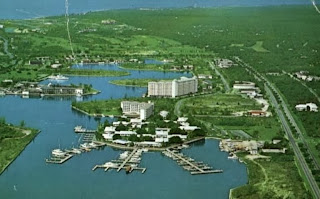

In the early 1950s, Hartford had “discovered” a 700-acre beach ten minutes by boat from Nassau called Hog Island. Measuring four miles by two-thirds of a mile, it got its name because it was overrun with pigs. Hartford bought it the same day he spotted it, never thinking it might be a good idea if his lawyers come down first to read the small print on his $11 million purchase. Hartford intended to develop the place into one of the world’s great tourist resorts. He renamed it Paradise Island and, over the next several years, dropped another $19 million trying to make it look like its new namesake.

At the heart of his plans was a hotel and casino complex. At the heart of his downfall was the fact that he chose the wrong law firm to advise him. Instead of going with Stafford Sands, he opted for honest lawyers and was, therefore, never able to acquire the necessary gaming license. Compounding the sin, Hartford sank money into the underdog, black power Progressive Liberal Party, which was tantamount to treason in the eyes of Sands and his white United Bahamians.

That Hartford soon ran into cash flow troubles simply exposed his carcass to the circling vultures. He was forced to sell part of his interest for $750,000. Inexplicably, Hartford then turned around and lent $2 million to the man who’d bought that part interest, accepting repayment in unregis tered stock, which he quickly discovered he couldn’t sell to anyone. So his new partner — the same fellow who still owed him $2 million — offered to help out with a $1 million loan, which wound up being secured with another hefty chunk of Paradise Island shares. The original guarantees were quickly pulled and the loan was called in. Hartford’s stake was sold and the net result was that his $30 million investment in Paradise Island produced a $28 million tax loss.

The group that moved in on Paradise Island was called Mary Carter Paint. They’d already tied up with Groves and Chesler in Freeport and would, in time, evolve into Resorts International. With Sands help, it was Mary Cater Paint that secured the casino license and saw Paradise Island rise out of Hartford’s ashes.

Lansky, in the meantime, was feeling the all-too familiar chill of political change. So he followed Hartford’s lead by quietly backing the Progressive Liberals. By the time the black Bahamian opposition just-barely squeaked into power in 1967, Sands was on his way into exile and the island’s new leader — Lynden Pindling — was on his way into the pocket of the great survivor, Meyer Lansky.

KINDLE: THE SINK http://amzn.to/132O2cE

Comments

Post a Comment